Inspections, border-crossings, varied modes of transport – all these add to the uncertainty of when produce will arrive. There are a huge range of risks in matching supply to demand. Supply chains can stretch from two days to many weeks. On any single day – the market – with its challenges of quality, timing and non-supply, struggles to fill retail shelves at acceptable customer prices.

The fresh supply chain is highly complex and fragmented – each actor in that chain deciding for themselves (with whatever market intelligence can be gathered, and based on its own judgment of what people want) what to grow and when. Budgeting and forecasting based on uncertain demand and supply is immensely difficult.

The challenges of fresh produce and the need to manage its passage through a complex supply chain has encouraged the food industry to embrace the opportunities of technology.

A WRAP report states that “The characteristics of the food system, such as complexity, huge geographical range, and diversity of operators make it particularly suitable for exploiting data-enabled technologies”.

In order to adapt and respond to this considerable change, there is significant expectation that technology will allow the fresh produce industry to prosper.

The way in which the market has adopted these technologies teaches us a lot about the best way forward.

Barcodes removed paper from the warehouses, as systems were developed to allow the movement of goods through warehouses to be integrated with scanning barcodes for inventory specific references (pallets/lots etc). This saved time and labour costs.

It is estimated that barcodes delivered 20% efficiency gains overall – and perhaps, just as importantly, added much increased accuracy of stock management and traceability of usage. Many companies share the same barcode labels through the supply chain, further reducing the cost of handling.

RFID removed the need to have someone scan a product, and could be read throughout the supply chain and read by sensors – but it failed in most markets. To provide the benefit, the warehouse had to be fitted with expensive sensors that could work throughout the warehouse or at entry and exit points, and had to work when faced with any warehouse and product conditions. The RFID technology required the entire supply chain to invest heavily to deliver its benefits.

This technology has been in place and has provided some benefits for more than a decade. The voice-directed system can be implemented to improve picking accuracy and the speed of the pick performed by the warehouse staff.

The voice picking system allows warehouse staff to concentrate on the picking process without looking at paperwork and having both hands free to perform the pick.

It has been calculated that this technology offers approximately a 5% gain over scanning but the benefits are only realised in high volume environments that are very labour intensive.

Technology has delivered incremental gains to the fresh produce industry over the last few decades. There have been promises of revolutions, but the reality has been that technology has delivered regular evolution and improvements of business processes.

The benefits of increased automation have not been fully realised across the supply chain and considerable opportunities still exist to improve processes, mitigate risks, and protect margins.

Whenever there has been a need for more than just a commercial relationship (shared cross supply chain coordination) – progress has normally been slow. Benefits are more likely to be realised by those companies that work through the details of processes on a day-to-day basis inside and take an evolutionary approach to delivering those benefits when applying new technology.

Technological implementations in previous decades have also highlighted the human challenge – there is natural desire to wait and see, to respond when competitors respond, or to hope that the change is fleeting and the status quo will be resumed. There is a substantial risk that inertia prevents fresh produce companies from fully exploring the opportunities enabled by new technology.

We are in the fourth decade of the commercial internet and its effect is everywhere – there are new opportunities to interact, to share information, to find and retain customers, to change, automate and improve business processes. These changes impact almost every aspect of our lives.

Data is exchanged faster and more accurately – far less data is rekeyed. This makes it easier to programme the connection between systems. There are substantial opportunities for richer, more accurate and faster data exchange between systems through the supply chain.

Cloud infrastructure has provided on demand data storage and computing power for a fraction of the previous costs, and allows companies to scale more quickly without building their own expensive computing systems and storage centres.

Internet era technologies offer the potential for what McKinsey have referred to as the digitisation of the supply chain. “The digitisation of the supply chain enables companies to address the new requirements of the customers, the challenges on the supply side as well as the remaining expectations in efficiency improvement”.

Blockchain is the disruptive kid on the block. Blockchain is a form of Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) – a chain of blocks that trace transactions and assets. The blocks are encrypted, carved, and timestamped by “miners” (a distributed group of “trustworthy” people who validate each transaction) and once incorporated in the chain, these transactions cannot be changed or removed.

Blockchain has the potential to enable supply chain participants to see all of the transactions relating to fresh produce, and allow consumers to understand exactly where their food has come from. For supply chain companies, this could provide “objective” stories of the life of any consignment and give much greater credibility and trust throughout the supply chain.

While blockchain does offer substantial opportunities for disruption, this technology and its effects are in their infancy.

SEE LINKED CONTENT:

Pathway to blockchain and artificial intelligence

Automation removes the need for humans to decide which buttons to push and when. Automation can drive significant change in the fresh produce industry by:

Eliminating tasks through automation requires:

The primary task is in knowing precisely what is happening and what the cost value and sale value is, as soon as possible, and as accurately as possible. There is a strong need for granular, pallet by pallet, consignment by consignment, inventory control for all aspects of data processing and reporting. All of the data necessary for any task has to be recorded and integrated: not in someone’s head or in an external document.

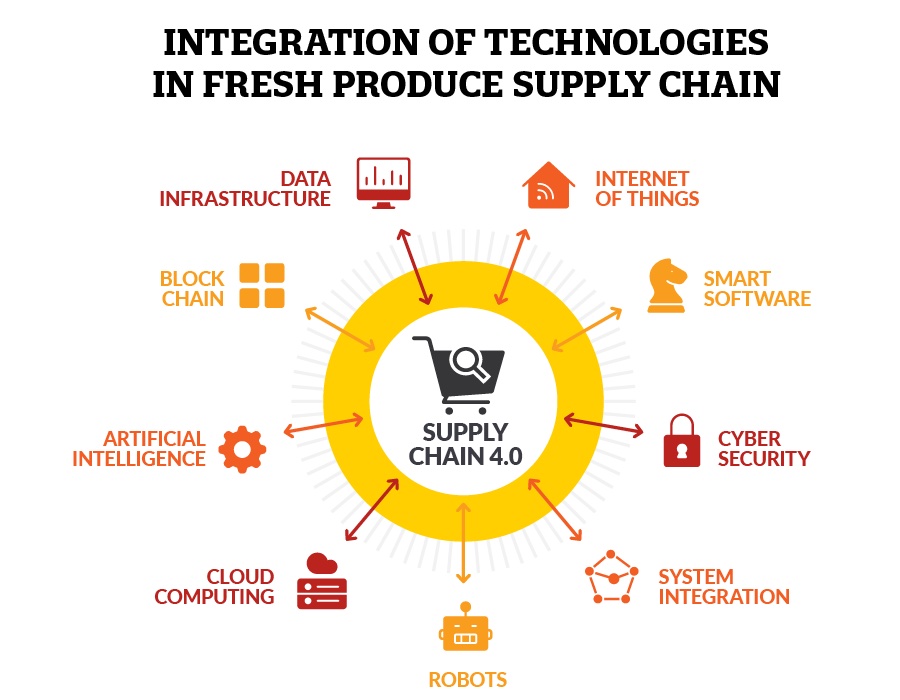

The Internet of Things (IoT) is defined as a network of physical objects or “things” embedded with software, sensors and network connectivity. These enable the IoT devices to collect and exchange data remotely across a network infrastructure.

IoT can have a significant impact on the fresh produce supply chain, especially in terms of food safety and traceability. By placing an autonomous IoT sensor in each pallet, food producers can automatically collect data about that pallet every minute. Sensor devices can help build an overall traceability picture of goods and products during their supply chain journey. Data from IoT devices provides a stream of high quality data that can be fed into smart software.

Current wireless infrastructure does not have the capacity to accommodate this number of devices and ensure exchange of information without minor lags. 5G connectivity will make it possible for sophisticated IoT tracking ecosystems that could transform logistics operations. High speeds and low latency will make it possible to gather real-time data, and to accumulate a more varied range of data across the entirety of the supply chain.

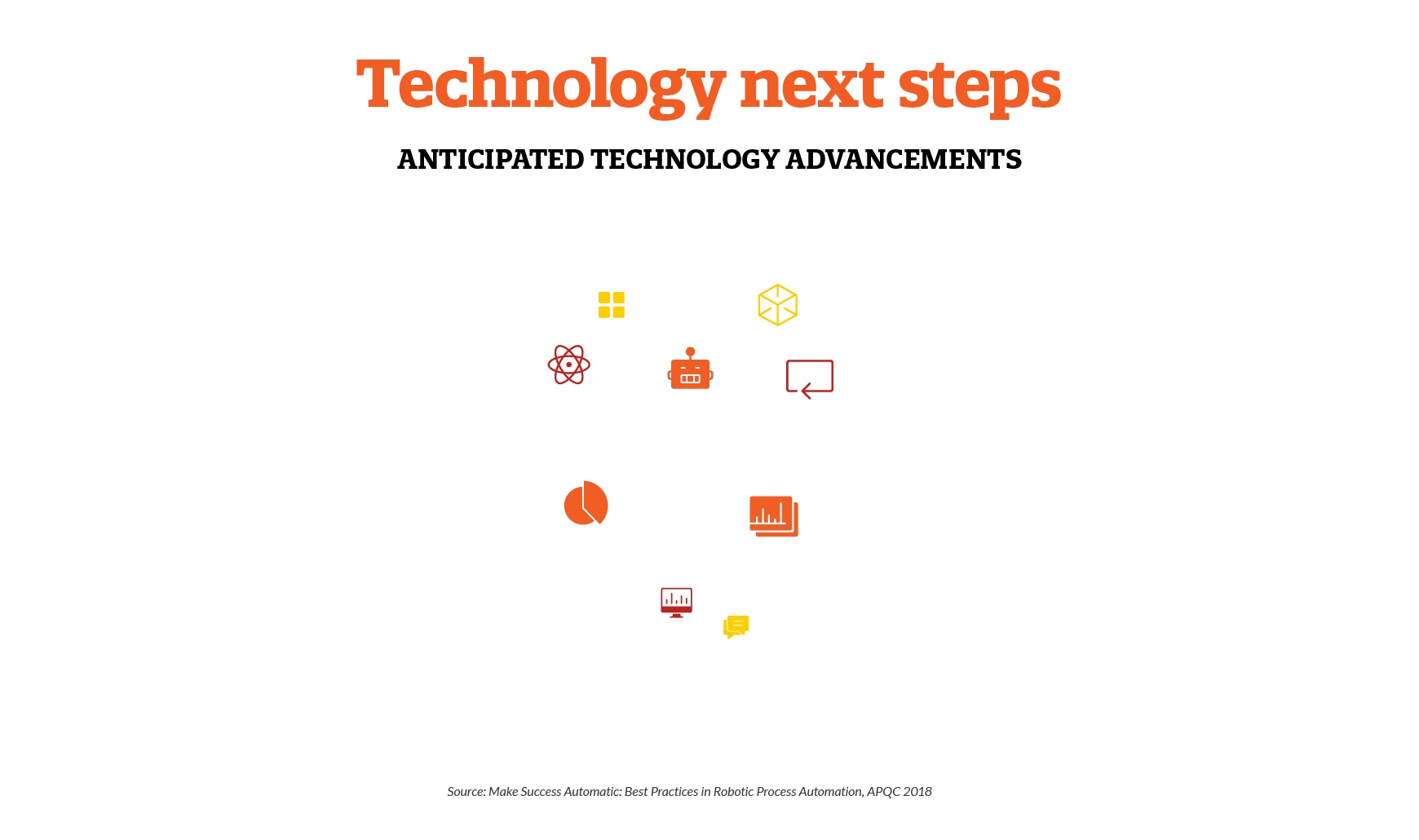

Robotic process automation (RPA) is a form of automation technology, sometimes referred to as software robotics.

Most automation tools require the use of Application Programming Interfaces (API) to script a series of mechanised processes; RPA systems watch the user perform tasks in the application’s graphical user interface and then perform the automation by repeating those tasks.

RPA has the ability to rapidly automate processes without the time and cost of developing more complex technical infrastructure; RPA is particularly well suited to working across multiple back-end systems. RPA is especially useful when the interactions are with older, legacy applications.

“Technologies like RPA are terrific tools for breathing new life into legacy systems and creating digital process flows, where before there was only spaghetti code, manual workarounds and swamps of data polluting the corporate underbelly”. Phil Fersht, CEO and Chief Analyst, HFS Research.

RPA is increasingly being used for more sophisticated purposes as bots become capable of smart decision-making based on pre-set logic.

A recent Forbes article stated that RPA is “a gateway drug to artificial intelligence”. The premise is that sophisticated RPA systems are capable of digitising business processes that had resisted automation up until this point, allowing a base layer of structured data that can be exploited for machine learning.

However, the simplicity of RPA’s approach means that it is unsuitable for dynamic environments with a large number of variables. RPA works best when application interfaces are static, processes don’t change, and data formats also remain stable – a combination that is increasingly rare in today’s dynamic, digital environments.

RPA does have a place in a corporate technology strategy when looking to rapidly move away from legacy systems and begin a journey towards a more automated supply chain. But without a robust data architecture that is able to incorporate new technologies, it should not be relied upon as a complete solution.

As defined by McKinsey, “Supply Chain 4.0’ is the application of the Internet of Things, the use of advanced robotics, and the application of advanced analytics of big data in supply chain management: place sensors in everything, create networks everywhere, automate anything, and analyse everything to significantly improve performance and customer satisfaction”.

Supply Chain 4.0 represents the complete digitisation of the supply chain and the collective application of many of the technologies that have been discussed. Supply Chain 4.0 is the culmination of a successful cloud-first, data-first, smart connectivity (Internet of Things) strategy that is able to capture, manage and iterate every process within the supply chain.

The benefits of the digitised supply chain relies upon a continuous process of improved planning and execution, as real-time data allows plans and processes to be improved through a multitude of feedback loops that drive improved performance.

McKinsey portrays Supply Chain 4.0 as “the highest digital maturity level, leveraging all data available for improved, faster, and more granular support of decision making. Advanced algorithms are leveraged and a broad team of data scientists works within the organisation, following a clear development path towards digital mastery.”

Artificial intelligence (AI), deep learning, and machine learning are often used interchangeably to describe the “science of getting computers to learn and act like humans do, and improve their learning over time in autonomous fashion, by feeding them data and information in the form of observations and real-world interactions”.

In the last decade, implementations of AI have become more widespread due to concurrent advances in computing power and the availability of large amounts of higher quality structured data. AI techniques seek to support the automation of repetitive tasks and an enhanced decision-making process.

Successful implementations of AI require deep implementations of data exchange and processing. Deep implementations of data processing are able to capture, in near real-time, every task that is required for the whole process flow of data through a single database. For fresh produce, this must be at the right level i.e. the level of the inventory reference which is the specific pallet within the specific consignment.

AI has the potential to improve supply chain management, including the quality and speed of planning insights. AI can optimise the reduction of waste associated with overstocking and understocking, improve delivered freshness of the product and streamline inventory management.